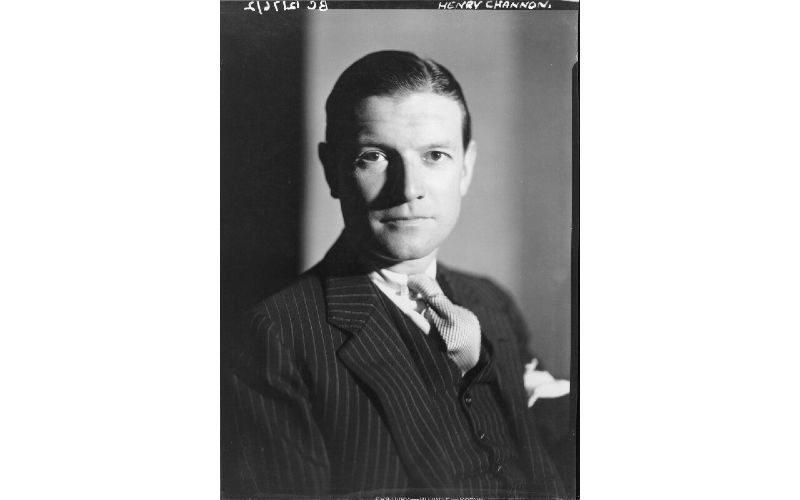

100 Heroes: Chips Channon

The gay man who became a well-connected politician.

Henry Channon, generally known as Chips Channon, was an American-born British Conservative politician, author and diarist. Channon moved to England in 1920 and became strongly anti-American, feeling that American cultural and economic views threatened traditional European and British civilisation. He wrote extensively about these views. Channon immersed himself in London society - actively seeking connections and making a name for himself.

Channon was first elected as a Member of Parliament in 1935. In his political career he failed to achieve ministerial office and was unsuccessful in his pursuit of a peerage, but he is remembered as one of the most famous political and social diarists of the 20th century.

Early years

Channon was born in 1897 in Chicago to an Anglo-American family.

After graduating from Francis W. Parker School and taking classes at the University of Chicago, Channon travelled to France with the American Red Cross in October 1917 and became an honorary attaché at the American embassy in Paris the next year. Channon associated with the artistic elite of Paris, having dinners with the writer Marcel Proust and poet Jean Cocteau.

In 1920 and 1921, Channon was at Christ Church, Oxford where he received a pass degree in French, and acquired the nickname “Chips”. He began a lifelong friendship with Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, whom in his diaries he called “the person I have loved most”.

Author

Channon rejected his American background and was passionate about Europe in general and England in particular. The US, he said, was “a menace to the peace and future of the world. If it triumphs, the old civilisations, which love beauty and peace and the arts and rank and privilege, will pass from the picture.” His anti-Americanism was reflected in his novel, Joan Kennedy (1929), described by the publishers as “the story of an English girl’s marriage to a wealthy American and of her attempts to bridge the gulf created by differences of race and education.” Channon’s anti-Americanism did not prevent his living off American money. A grant of $90,000 from his father, and an $85,000 inheritance from his grandfather made him financially comfortable with no need to work.

He wrote two more books: a second novel, Paradise City (1931) about the disastrous effects of American capitalism, and a non-fiction work, The Ludwigs of Bavaria (1933) - a study of the last generations of the ruling Wittelsbach dynasty of Bavarian kings.

Marriage and politics

In 1933, Channon married the brewing heiress Lady Honor Guinness. In 1935, their only child was born, a son, whom they named Paul.

In 1936, the Channons moved into a grand London house on Belgrave Square, and subsequently acquired a country estate, Kelvedon Hall, at Kelvedon Hatch near Brentwood in Essex.

Channon quickly established himself as a society host.

At the 1935 general election, Channon was elected as the Member of Parliament for Southend, the seat previously held by his mother-in-law Gwendolen Guinness, Countess of Iveagh.

In the period leading up to WWII, Channon favoured appeasement, a position probably shaped by his friendships with European aristocrats.

At the invitation of Joachim von Ribbentrop, Channon attended the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics.

Personal life

Channon had numerous relationships with men throughout his life.

In 1939, Channon met the landscape designer Peter Daniel Coats, with whom he began an affair that led to Channon’s separation from his wife the following year and the dissolution of the marriage in 1945.

Among others with whom he is known to have had relationships was the playwright Terence Rattigan, Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, and the Duke of Kent.

Diaries

At various points in his life Channon kept a series of diaries.

Under the terms of his will, he left his diaries to the British Museum on the condition that they would not be published until 60 years after his death.