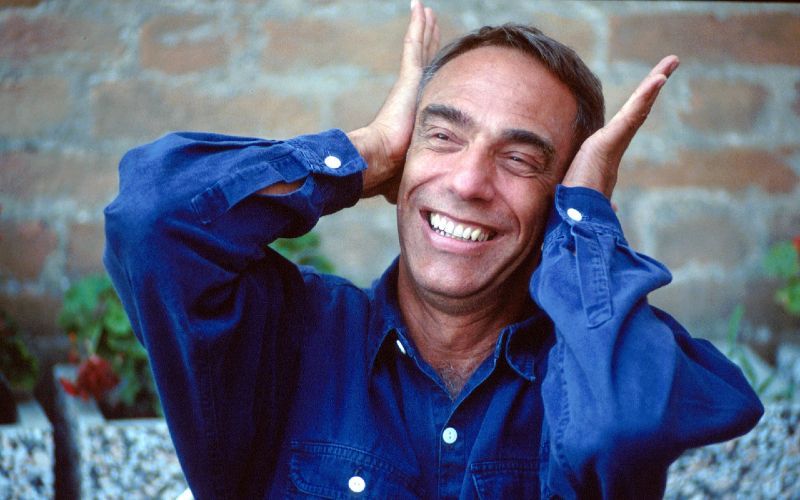

100 Heroes: Derek Jarman

The gay man who became an iconic queer film-maker.

Derek Jarman was renowned as a gay rights activist. His best-known films include Sebastiane, Caravaggio, and Edward II.

He died in 1994.

Jarman was creatively, politically and personally motivated, and he pursued his interests with enormous energy and individual vision.

His films were works of art but also engaging pieces of cinema in their own right.

A fiercely queer filmmaker, Jarman's films challenged what was possible in terms of queer representation on screen. He was radical and his films challenged audiences but he also achieved mainstream recognition.

Images from Jarman's film, Caravaggio

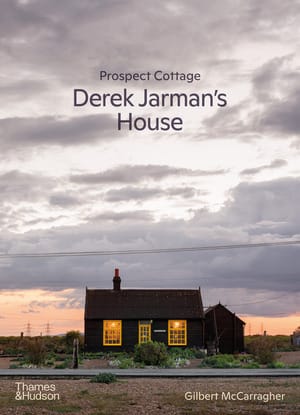

Prospect Cottage

Giving us a glimpse into the personal sanctuary of Derek Jarman, Gilbert McCarragher's book explores the interior world of the iconic artist.

Prospect Cottage: Derek Jarman's House lovingly documents every inch of the small home that Jarman created in Dungeness, where he lived with his partner Keith Collins.

After Jarman's death in 1994, Collins continued to live in the cottage - tending to the gardens.

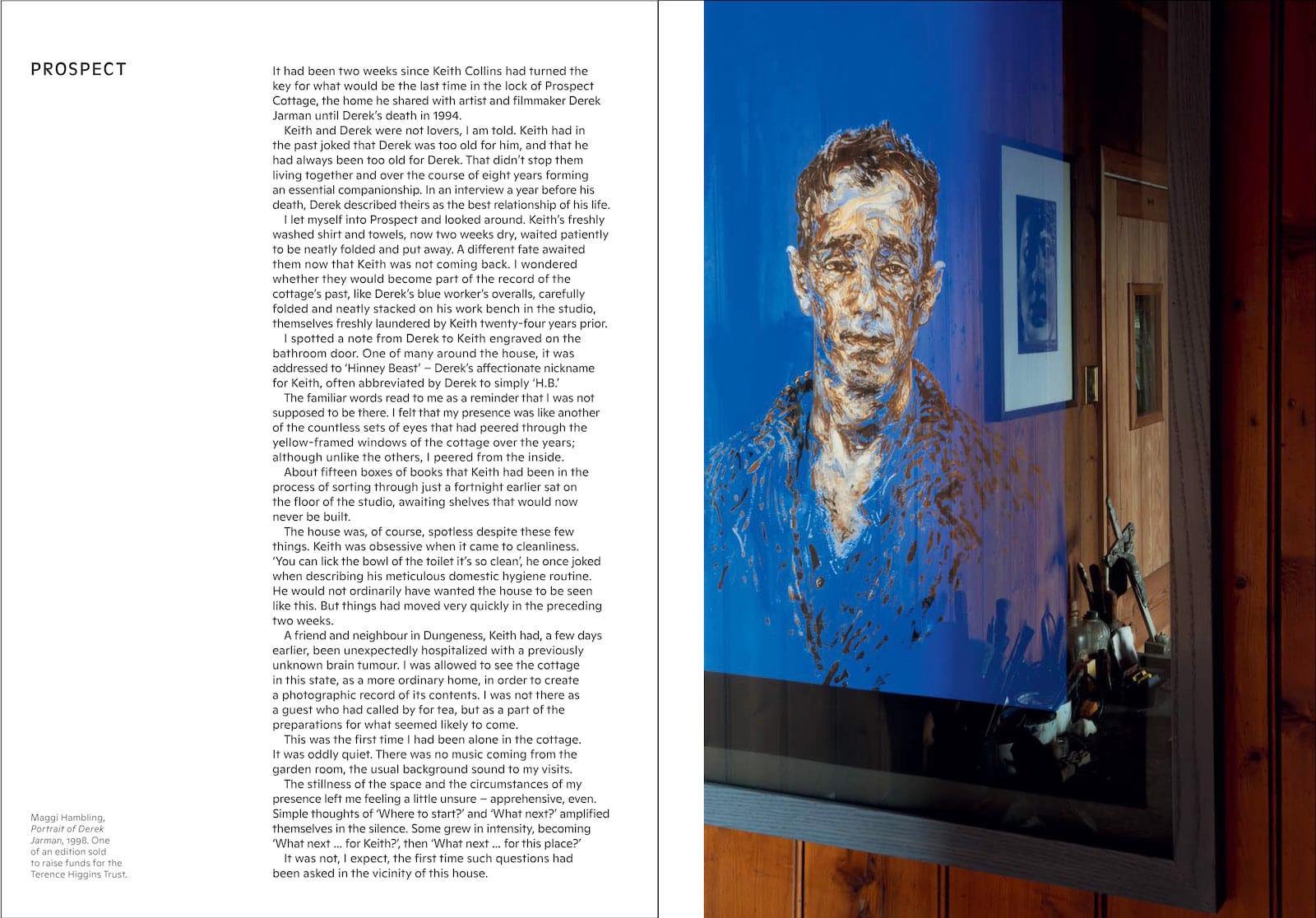

Collins died in 2018, and McCarragher - a friend and neighbour - was asked to turn his camera on the life that Jarman and Collins had built inside Prospect Cottage. This was the first time that the interior of the property has been documented as an artwork in its own right.

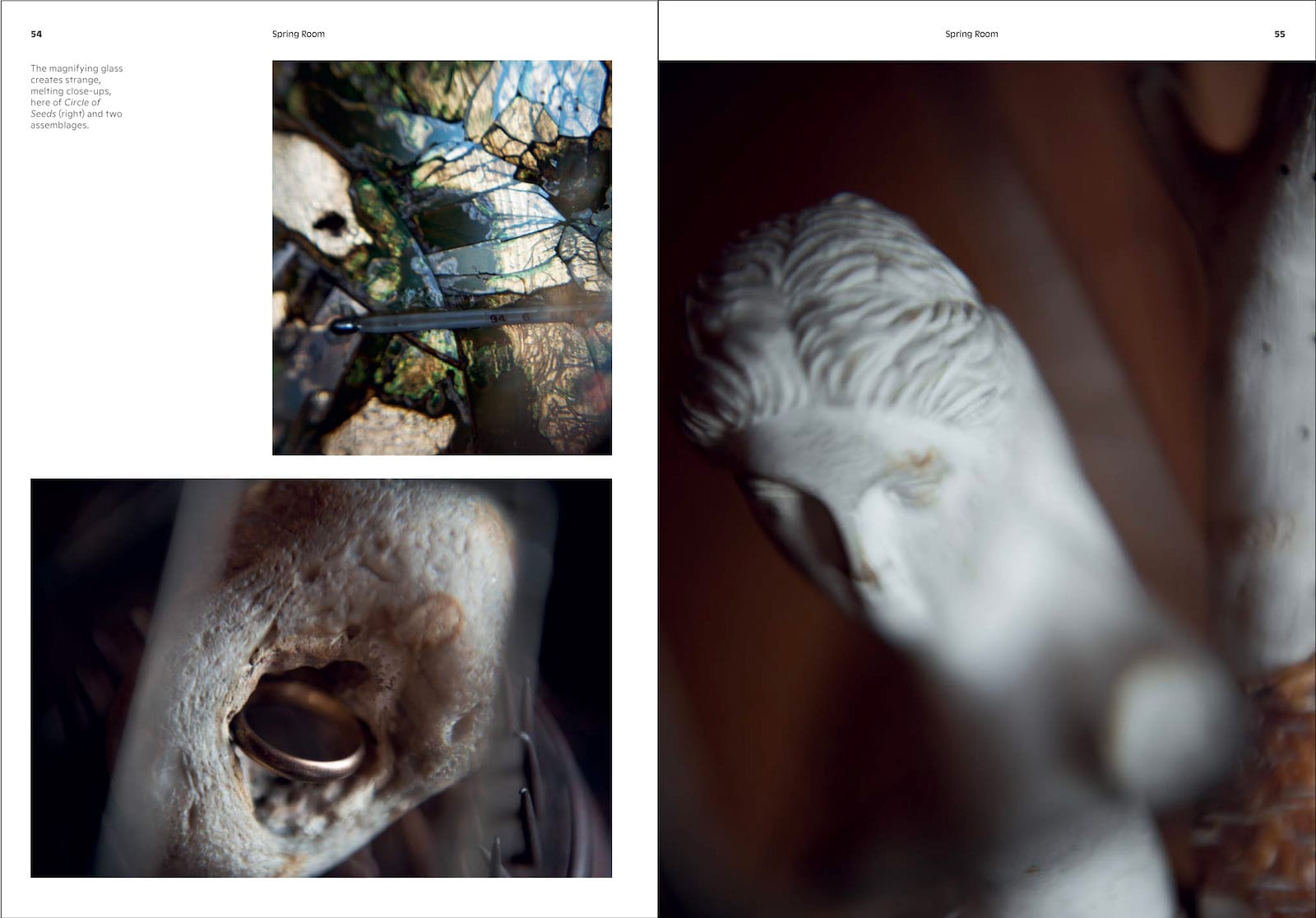

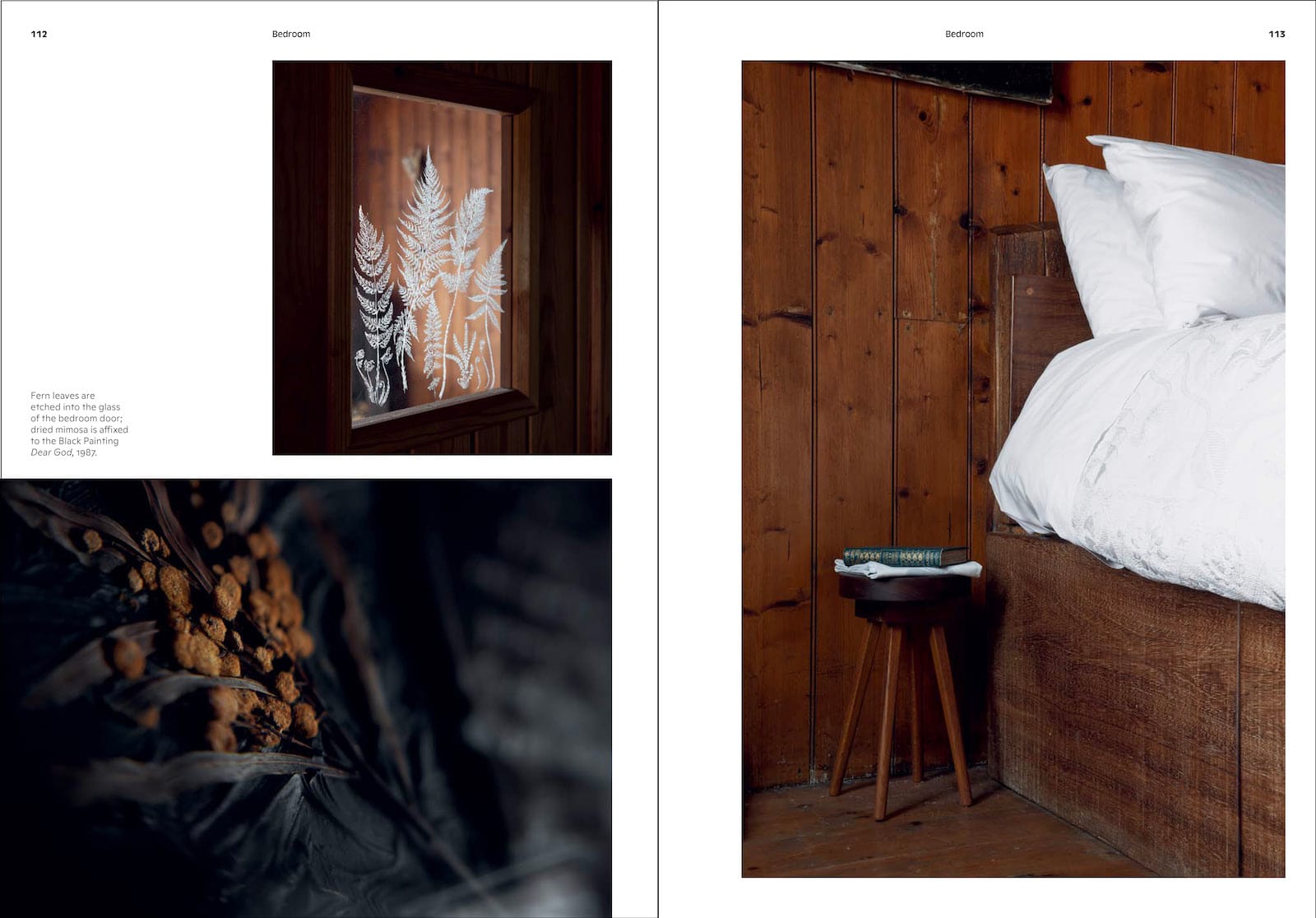

The resulting book features 160 photographs accompanied by reflective essays that help provide some context as to the importance of Jarman's work in shaping the UK's queer landscape.

For our podcast, we spoke with Gilbert McCarragher about the project.

Photos from the book