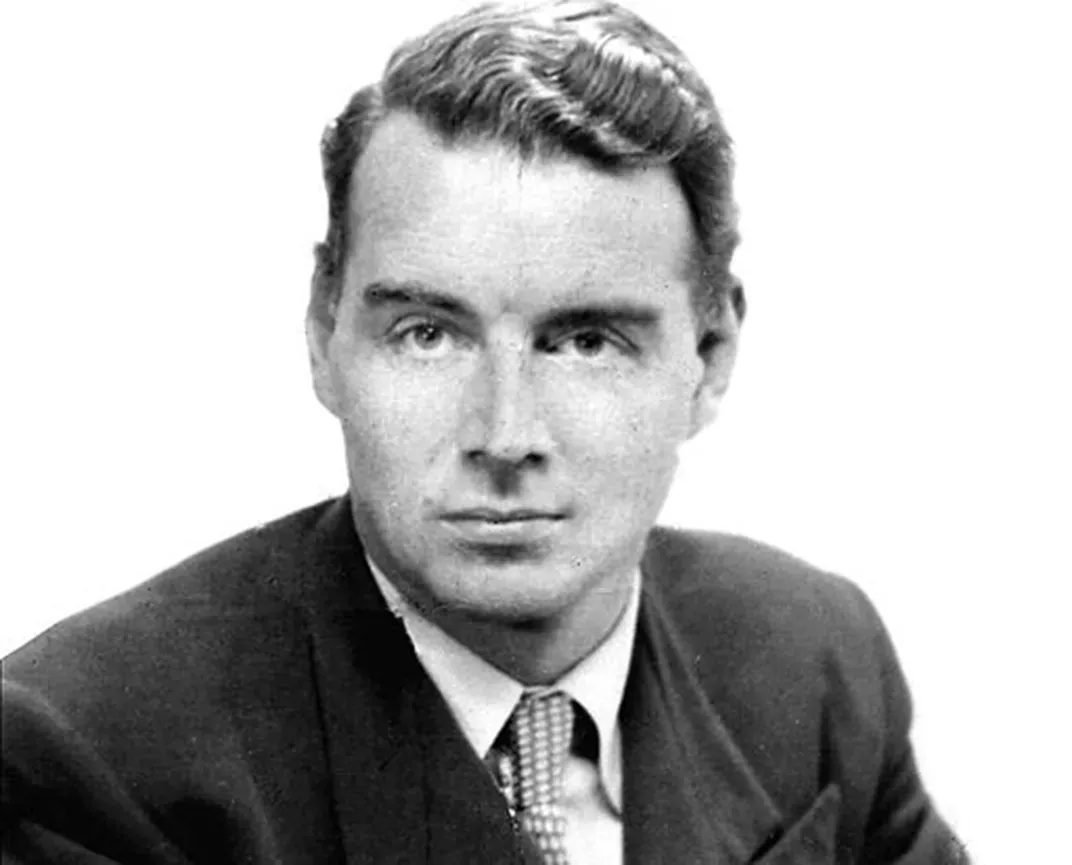

Villain Edit: Guy Burgess

An impactful double-agent at the height of the cold war.

Guy Burgess was a British diplomat and Soviet double agent, and a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era.

Biography

Born in 1911, Burgess came from an aristocratic family.

He was schooled at Eton before joining the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth. He was adept at building a network of contacts that would prove useful later in life.

At Eton, sexual relationships between boys were common, and Burgess confirmed that he had numerous sexual encounters while at school.

He went on to study at Cambridge.

He embraced left-wing politics at Cambridge and joined the British Communist Party.

Burgess by this time made no attempt to conceal his homosexuality. In 1931 he met Anthony Blunt, four years his senior and a Trinity postgraduate. The two shared artistic interests and became friends, possibly lovers.

Burgess was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1935, on the recommendation of the future double agent Harold "Kim" Philby.

Late in 1935, Burgess accepted a temporary post as personal assistant to John Macnamara, the recently elected Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Chelmsford. He and Burgess joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, which promoted friendship with Nazi Germany. The association with Macnamara involved several trips to Germany; some, by Burgess's own later version of events, involving sexual trysts–both men were gay and sexually active.

In 1936, Burgess met the nineteen-year-old Jack Hewit in The Bunch of Grapes, a well-known gay bar in The Strand. Hewit, a would-be dancer seeking work in London's musical theatres, would be Burgess's friend, manservant and intermittent lover for the next fourteen years.

Burgess joined the Foreign Office in 1944.

At the Foreign Office, Burgess acted as a confidential secretary to Hector McNeil, deputy to Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin. This post gave Burgess access to secret information on all aspects of Britain's foreign policy during the critical post-1945 period, and it is estimated that he passed thousands of documents to his Soviet controllers. In 1950 he was appointed second secretary to the British Embassy in Washington, a post from which he was sent home after repeated misbehaviour. Although not at this stage under suspicion, Burgess nevertheless accompanied fellow spy Donald Maclean when the latter, on the point of being unmasked, fled to Moscow in May 1951.

Burgess's whereabouts were unknown in the West until 1956, when he appeared with Maclean at a brief press conference in Moscow, claiming that his motive had been to improve Soviet-West relations. He never left the Soviet Union; he was often visited by friends and journalists from Britain, most of whom reported a lonely and empty existence. He remained unrepentant to the end of his life, rejecting the notion that his earlier activities represented treason. He was well provided for materially, but as a result of his lifestyle his health deteriorated, and he died in 1963.